Brussels, 2024

MORE ABOUT US

It's all about the light. The decision was inevitable: of course, we had to buy the house.

Raconteurs like me revel in the darkest corners of dimly lit, wood-paneled rooms, lounging in chocolate-colored Chesterfield fauteuils under a floor lamp with the cheapest of lightbulbs that should have been replaced years ago. That's where reality—at least my misconstrued version of it—keeps unfolding in my head, with a drop of single malt to lubricate every nut and bolt needed throughout the process.

Créateurs like her need light. Firmin Baes was like her.

It was 1906 when he built the house, with which we fell in love. As a professional painter known for his extraordinary pastels, light was his instrument of choice, and the bourgeoisie in Brussels was his preferred clientele. Unfortunately, this clientele would soon shift their preferences from traditional painted portraits to the emerging technology of photography, unforeseen by Mr. Baes. The 3-centimeter gap under the doors on the first floor testifies that he ran out of money. The pine subfloors were never finished with the same tongue-and-groove oak parquet as the ground floor. But it is just as beautiful.

There's nothing new about disruption.

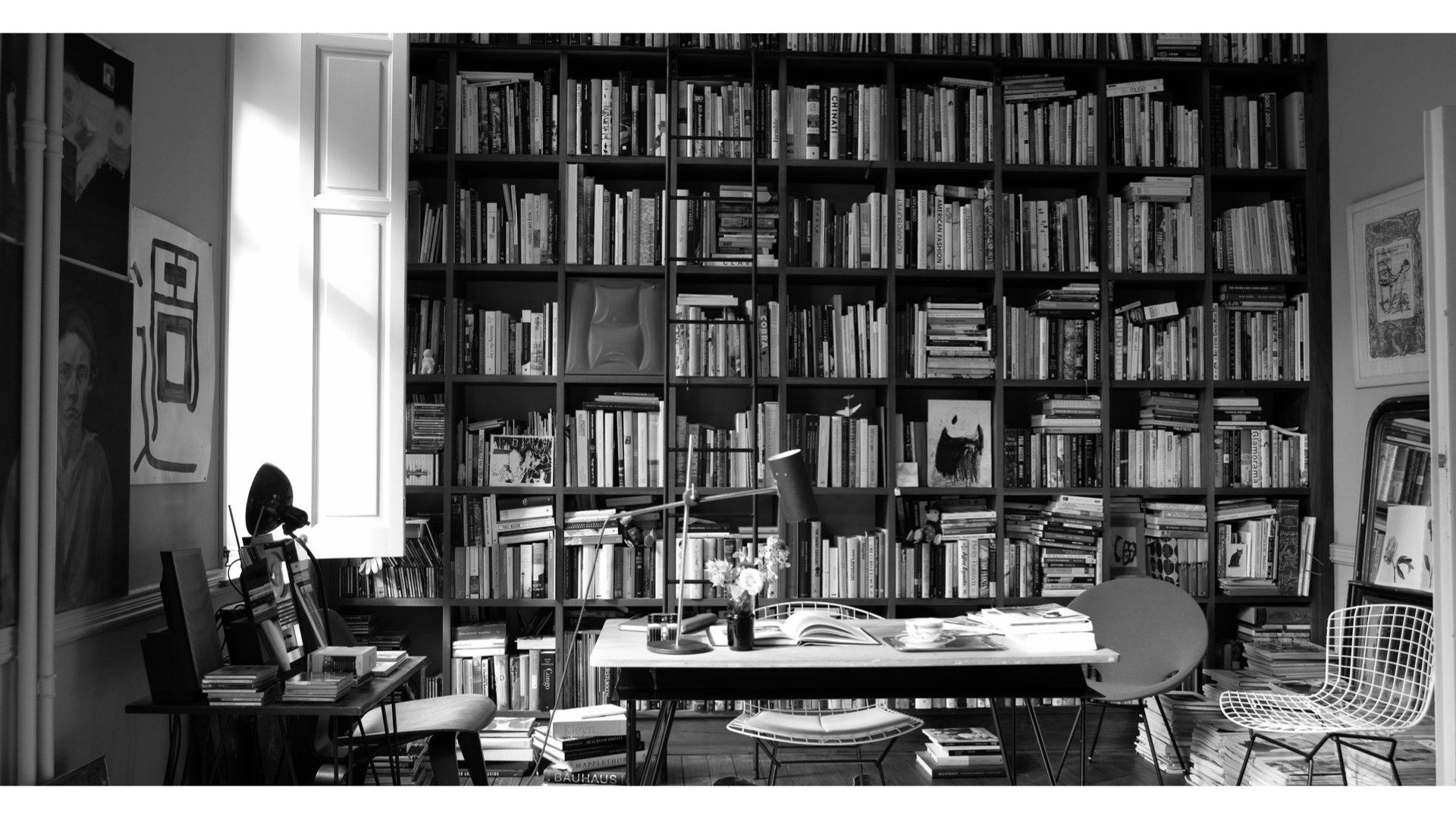

We cherish the gap under the doors and continue to live on the pine subfloors of the first floor. Its single planks run the entire width of the house and are part of the meticulous restoration of Firmin Baes' house with respect for its history. It is still a hub for creativity and creation, and we filled it over the years with a playful mixture of art, mid-century furniture, books, magazines, photos, and the artworks that our children created when they were young. All blend in, even some of Brussels' new bourgeoisie, mostly those with a bohemian streak.

Natural light still streams through the bay windows at the front and back, as well as through a huge skylight. The environment is by no means minimalist, but in a very personal way, it feels as if every object found its place organically and harmoniously. Every single item in our house radiates inspiration.

We rely on its inspiration every day. It's our work environment when we are not traveling.

Some find it chaotic, but we don't. A formal classification system for the thousands of books and magazines is absent by design and lack of time. We find the sensation of discovering forgotten publications far more stimulating than the efficiency of sterile categorization. You're looking for Auster, and you find yourself submerged for hours in Veronesi's Quiet Chaos again.

"I'm with Pierre," she said matter-of-factly during our call, "and I'm buying a house."

Pierre was a friend who restored houses. It wasn't exactly the reply that I anticipated. We had run out of cash, were deep in debt, still hadn't finished the restoration of our Brussels home, and my business was under threat of a hostile takeover.

"Not the right time," I replied, irked. "And give my regards to Pierre."

I believed that I still had a slight chance of influencing a decision that Reinhilde intended to make or had already made. That was the past. I'm a wiser man now.

We spoke kindly to our banker and followed through on our whim to buy the house in Waulsort, a quaint village along the Meuse River where rich Belgian industrialists built their summer residences in the early 1900s. The tiny farmhouse was constructed around 1830 and belonged to the village's only horse carriage driver. He doubled as the undertaker, driving the horse-drawn hearse.

Microjobs already existed in the 19th century.

Here, life unfolds outdoors; the weather sets our agenda, and the lavish garden dictates our activities. In contrast to the dominance of nature that envelops it, the house fits like a warm glove with its wood-fired design stoves, its subdued color scheme, its vintage furniture, and its subtle decoration.

Waulsort is only a 90-minute drive from Brussels. The city gives way to the countryside. You'd expect the two separate worlds to collide, but they don't. Both houses are equally inviting, seamlessly connected by Reinhilde's coherent design principles applied during their restorations.

So why travel?

Travel teaches us the art of not taking things for granted, compelling us to embrace new situations and accept differences, keeping our minds agile and our spirits adventurous. We learned more about America from speaking to ranchers at a cattle market in Central Florida than we could ever have learned from reading about the US in the New York Times or on Twitter.

We rarely travel because of a destination. We mostly travel because of a house—a distinct place with an undeniable appeal that we can get acquainted with. These houses become more than just temporary shelters; they are our homes, where we immerse ourselves as locals, living and working amidst their walls filled with stories. They permit us to observe and document the beauty of the people and their surroundings that lurks hidden, that is masked or shy, and that tries its best not to be noticed.

And we travel toward the light.

Because that's what créateurs crave. And for raconteurs like me? We spin our tales by the glow of a dim floor lamp, its bulb long overdue for a change, sustained by just a drop of something fine to keep the narrative alive.

Subscribe to get full access to the newsletter and publication archives.